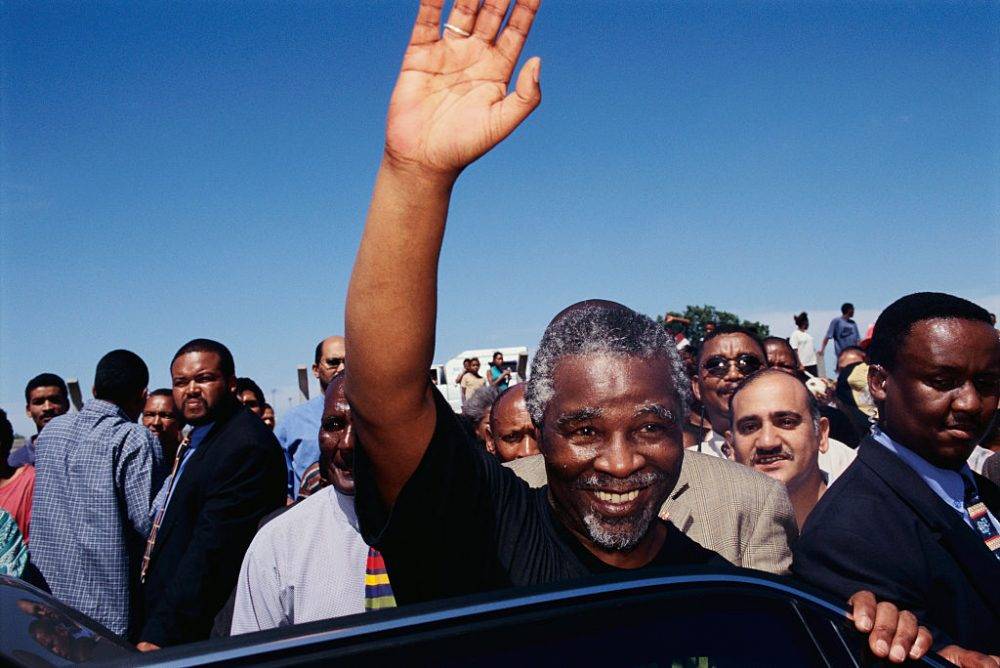

Presidential candidate Thabo Mbeki waves to supporters while campaigning near Cape Town, South Africa. | Location: near Cape Town, South Africa. (Photo by © Louise Gubb/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

So, it’s all over. And frankly, thank goodness for that. Elections are a necessary — though often engaging — evil. It was not that this campaign consumed so much energy and resources, or even that it was so dull at times, but that its superficiality was so depressingly bestial.

“Hang murderers! Kill the rapists!” screamed the lamp-posts, representing the not-so-thin edge of a thick and ghastly wedge; next time round it will be “Chop off the hands of thieves!” Most of the opposition parties appeared to have entered a bloodthirsty competition to prove to the electorate that they were the toughest on crime and criminals; an appalling contest of machismo rather than of ideas.

At least British Prime Minister Tony Blair has always proclaimed that he is “tough on crime and tough on the causes of crime”. Here the cause — poverty — and the vexed questions around how best to alleviate it were invariably conspicuous by their absence. To the extent that the African National Congress, at least, sought to confront the real policy challenges, it deserved to win. Is the fact that it won so well a comfort or a threat? That, to many, becomes the important question for the future.

The short and trite answer is to say, well, that depends on how the ANC uses — or abuses — its power. The longer and more profound answer requires an examination of the condition of the democratic polity within which the ANC will exercise its replenished authority to govern.

But first the easy bit: it was fair, it was free, and it was pretty calm and peaceful. To those looking from afar, it will confirm their view that South Africa is a consolidated and fully functioning democracy.

This exposes a central problem with elections in transitional societies: the actual electoral process can eclipse the more fundamental democratic challenges. The fact that things went smoothly does not alter the fact that, according to our attitudinal surveys, one in four South Africans would be prepared to intimidate a political opponent in his or her community. South Africa is still a deeply wounded and violent society.

Nor does it alter the reality that a culture of rights still needs to be built to give life to the values that underpin the Constitution; that the efficacy of the various independent institutions of democratic governance is clouded by uncertainty about their role and funding, and their relationship with the government still uneasy; that the system of representative democracy that has been created is obscure to many, rendering meaningless the constitutional articulation that South Africa’s is a participatory as well as a representative democracy.

For those who are worried by the size of the ANC’s victory, it should be a comfort to recognise that a large majority reduces the likelihood of a populist shift in ANC policy- making. Capital punishment, for example, is less likely to return because the ANC won so decisively.

Indeed, the central irony of the campaign was that while the main opposition parties eagerly sought to make the two-thirds majority “threat” a major source of anti-ANC votes, it is the ANC that is the more likely to protect the human rights basis of the Constitution against those ignorant fools who believe that it is the Bill of Rights rather than ineffective police detection that explains why criminals run amok.

All of this exposes the deceit of liberal democracy, according to which a free and fair election and multi-party democracy is all you need. South Africa has just proved that it has both. The fact that the opposition parties performed so ineptly that they were unable to capitalise on the decline in individual identification with the ANC after 1994 does not alter the fact that they had a full opportunity to compete.

Some liberals are honest enough to admit that it is not the taking part but the winning that matters; that it is the rotation of power — or at least the real possibility of it — that is both significant and necessary.

Even former liberals such as the born-again conservative Tony Leon speak in these terms. Towards the end of the campaign, in a desperate attempt to convince the Democratic Party’s (DP) former core constituency, and apparently himself, that he is still a liberal, Leon argued that the ANC “is affronted that there should exist in this society a genuine, confident, unapologetic alternative”.

No doubt this would have attracted the 10 (out of 12) white Johannesburg golfers who on Wednesday told the BBC that the election was about “strong opposition”. But did his reactionary “fight back” campaign achieve anything other than an increase in the (still modest) percentage of the popular vote cast for the DP?

Put in wider terms: did the pluralism of the election campaign serve the needs of the majority of South Africans? Did the ostensible array of choices serve the quest for the right policies to reduce unemployment and alleviate poverty? If so, it is very difficult to see how.

The Constitution is, in the words of constitutional court Judge Kate O’Regan, a document of transformation, at the heart of which lie various extraordinary social and economic rights. The government is enjoined to progressively realise the rights to adequate food and housing, health care, education and social security. These rights are unique to South Africa and set an appropriate, but demanding challenge.

The grand dilemma for the government is how to increase power without diluting accountability in the face of such challenges.

Hence, the search for “strong opposition” entirely misses the point. The liberal notion that rotation of power is good for democracy needs to be subjected to serious scrutiny. Why should the rotation of power produce either good, accountable government or good, clear, long-sighted policy-making? The comparative experience suggests the opposite.

My former boss, Wilmot James, the head of the Institute for Democracy in South Africa, got into an unedifying row with president-elect Thabo Mbeki at the end of last year when his view of the Mbeki presidency as likely to be “tougher and [yet] more obscure” leaked out.

The clumsiness of the expression and his handling of the response to the assault from Mbeki’s office colluded with the context to permit a solely negative interpretation. I prefer a more positive one: modern government is about being decisive — and tough — in the face of powerful countervailing forces. Whether you achieve that objective by obscurity or by transparency in your political management is, of course, another matter.

Hence, the test for the next five years has two distinctly uncertain dimensions.

The first uncertainty is whether the maturation of the new system of democratic governance with its bright but troubled array of state-of-the-art democratic institutions, is deep enough to secure accountability in the use of power.

The second asks whether the electoral authority that has been conferred upon the ANC is matched by sufficient power in government to achieve what the Constitution demands of it by way of radical social and economic transformation.

Thus, the weight of the ANC’s electoral victory need not be an issue of burning concern. The ANC is, conclusively, still in office. Now, however, it must prove that it is in power as well.

In 1999, Richard Calland headed the Institute for Democracy in South Africa’s Political Information & Monitoring Service.

2 weeks ago

86

2 weeks ago

86