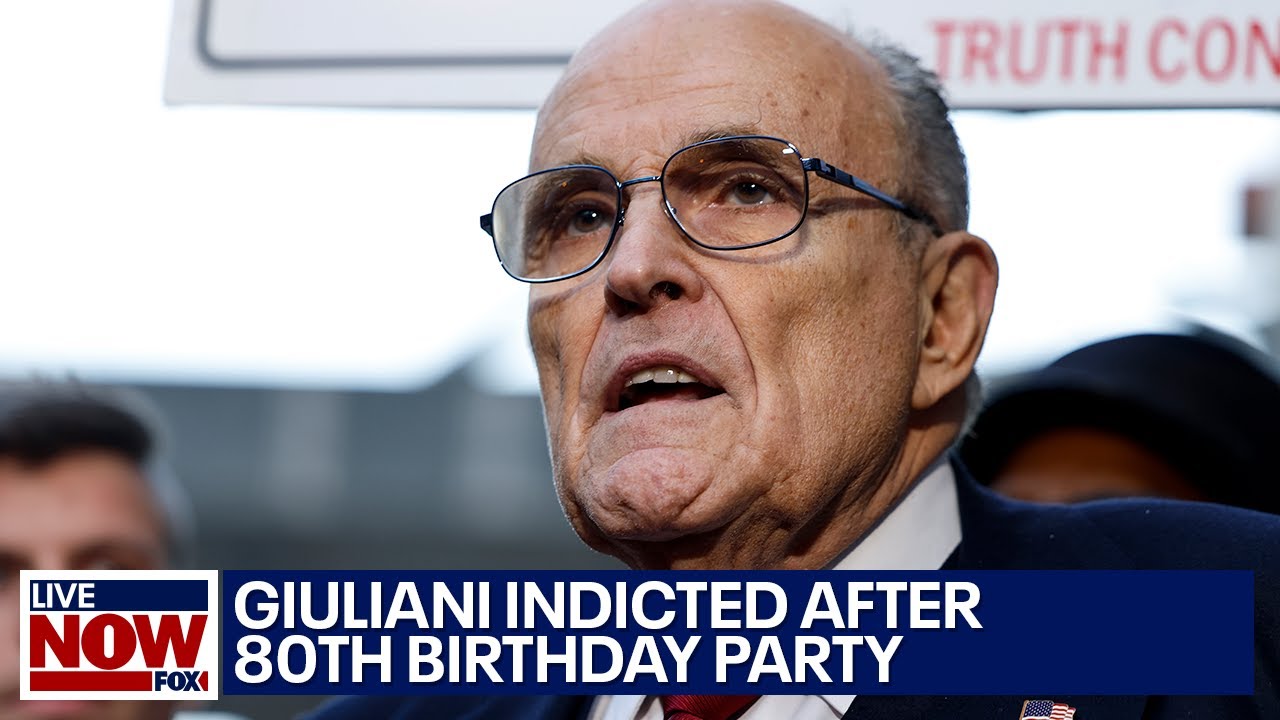

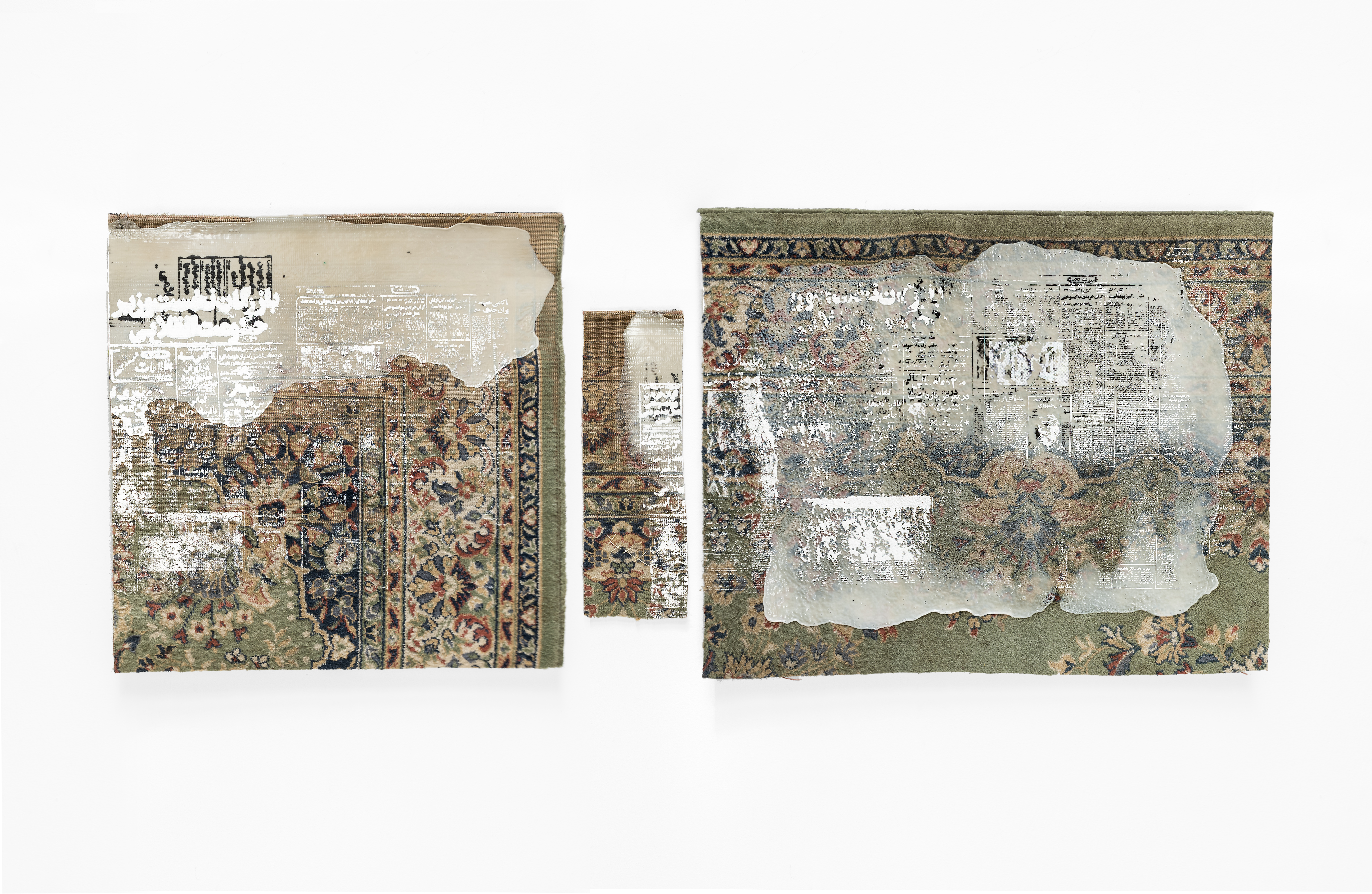

It’s the glue that stands out first. Embedded in the fibres of a Persian carpet, this frozen spillage appears at first to be a tragedy in miniature. But there is an alchemy at work, and a set of subtle changes taking place. Here, glue becomes a secondary canvas bearing text and imagary, and the rug becomes a soft sculpture — a complicated landscape. In and amongst it all, a patch of gold leaf glistens optimistically.

Tehran-born, Cape Town-based artist Sepideh Mehraban has been working with Persian rugs for some time now, salvaging them from auction houses and second-hand stores, and giving them new life as layered art objects. Items of cultural significance — every household in Mehraban’s home country of Iran has one — they’re objects that are alive with love and labour, and bristling with a hand-woven history of women’s labour.

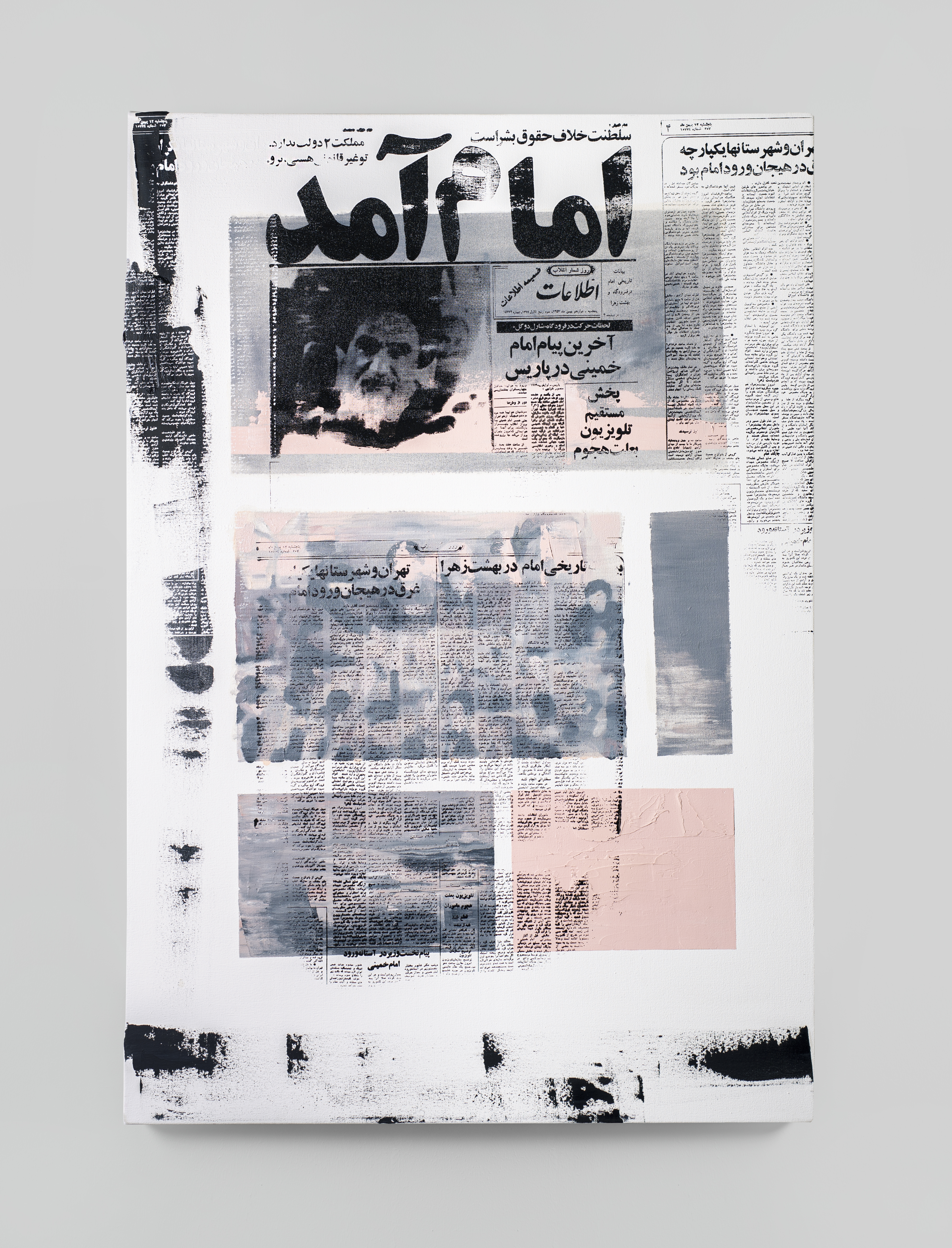

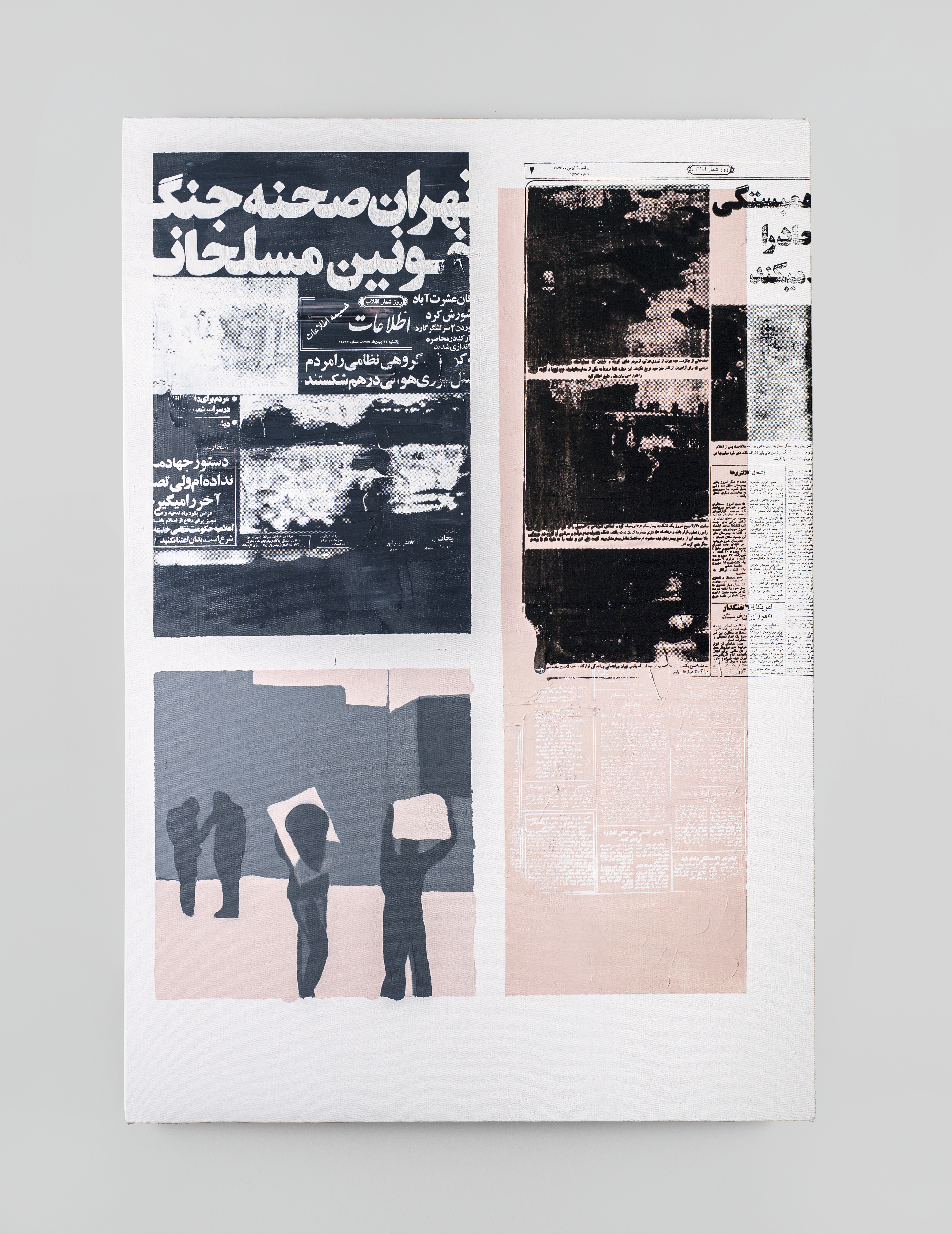

Sepideh Mehraban, ‘Prime Minister’, 2019, Mixed Media on carpet. Part of the artist’s ‘This is not Propaganda’ exhibition at SMAC Gallery. (Photo: Supplied)

“I haven’t travelled back home since 2018,” says Mehraban, standing in front of a large-scale Persian carpet trailing down the wall of her light, bright Woodstock studio. It’s February in Cape Town and the city is alive with the annual Investec Cape Town Art Fair.

Since obtaining her Masters in Fine Arts at the University of Alzahra in Tehran in 2011, Mehraban has been based in Cape Town. It was in 2012, during a holiday visit, when she met Virginia McKenny who later became her supervisor during a second Masters in Visual Arts at the Michaelis School of Fine Art.

“12 years later and I’m still here,” she smiles.

Returning home is difficult. Iran’s authoritarian state has seen years of protests, fuelled by economic grievances and, more recently, calls to end the Islamic Republic. The Iranian government’s response to protest action over the years has been brutal. Activists are routinely jailed and met with violence from the state. In 2022, the death of 22-year-old Mahsa Amini in police custody ignited a long-standing anger from Iranians around religious laws. Amini was arrested on an accusation of violating the hijab law, in effect since 1981 following the 1979 Iranian Revolution.

Though critical of the Iranian government, Mehraban was always careful about how public her critique was. In 2022, however, she felt she could no longer remain silent.

‘Thread of Stories’ installation by Sepideh Mehraban for the ‘Eyes on Iran’ project. (Photo: Supplied)

“Nobody is really supporting the government, I mean it’s such a small minority that supports them, but they remain in power. Everyone is unhappy, the economy is crashing, there are so many social issues. On every level the country is suffering,” she says.

In November 2022, Mehraban was one of 10 artists to activate New York’s FDR Four Freedoms State Park with a multi-media art installation facing the United Nations entitled Eyes on Iran. Other artists were Shirin Neshat, Mahvash Mostala, and Hank Willis Thomas. For Mehraban, it was an essential moment, a means of putting art to work as a tool for change.

‘Thread of Stories’ installation by Sepideh Mehraban for the ‘Eyes on Iran’ project at the Franklin D Roosevelt Four Freedoms State Park, across from the United Nations in New York. (Photo: Supplied)

That same year, she hosted Birds for Freedom at her Woodstock studio, a project led by Nava Derakhshani, and joined by Kamyar Bineshtarigh, both fellow Iranian artists based in Cape Town at the time. Taking their lead from protesting Iranian art students and the Japanese proverb ‘When you fold a thousand cranes, your wish will come true’, they sat in Mehraban’s studio and folded paper birds in community with fellow Iranians and allies. The birds were later exhibited as an installation in The Old Granary Building in the city.

By the time she held her 2023 solo at WHATIFTHEWORLD gallery, Mehraban had started using her art as a clear and committed platform against erasure. “This time women’s bodies and voices can not be obliterated from history, as they are in the front line of fighting for freedom,” she said in her exhibition statement for Give me liberty or give me death.

Propaganda, censorship, and the ways in which governments control information and public life are points of interest for Mehraban. She works with reproduced newsprints from 1979 — propaganda tools by the Iranian government — which have long provided material for her work, showing up in her prints and paintings as textual vignettes and collage-like fragments.

‘Thread of Stories’ installation by Sepideh Mehraban for the ‘Eyes on Iran’ project at the Franklin D Roosevelt Four Freedoms State Park, across from the United Nations in New York. (Photo: Supplied)

Here, multiplicity is key, as is the notion of equivalence. The parallels between post-revolution Iran and post-apartheid South Africa serve as a touchpoint for the artist — a case study for countries that promised their citizens better lives but let them down on fundamental levels.

Though she wasn’t born when the revolution took place, Mehraban grew up listening to her parents reflecting on it. “I became interested in how we Iranians live this dual life, this parallel life that’s very different to what the government dictates to us.”

She recalls a particular moment from her childhood, prompted by a family photograph of Mehraban in the garden, dressed in a pink outfit and smiling at the camera: “In the 80s when they were killing activists, I was at home eating cherries with my mom and playing in the garden”. The photograph, she says, was taken in the same year as the political executions in Iran.

Sepideh Mehraban, ‘Messenger’, 2021, Mixed Media on Canvas. Part of the artist’s ‘This is not Propaganda’ exhibition at SMAC Gallery. (Photo: Supplied)

This kind of bittersweet mnemonic is at the heart of Mehraban’s work. Tragedy and triumph, beauty and disaster, suppression and resistance, history and memory all tussle and jostle up against one another to provide a fuller narrative of contemporary Iranian life.

Lately, her work has taken on an enduring optimism. In a recent solo show at Johannesburg’s Goodman Gallery, Mehraban presented a selection of new paintings.

Alive with colour and spirited gesture, the works in Promise of Paradise are a combination of oil, acrylic and gold leaf on canvas. Her engagement with the canvas is multidisciplinary. Bright orange impasto daubs sit alongside thin layers of white paint, printed into and impressed upon with Mehraban’s signature archival materiality.

‘Promise of Paradise’ installation at the Goodman Gallery, Johannesburg. (Photo: Anthea Pokroy)

As a result, the works manage to hold great poetry and pragmaticism in a single frame. Half-formed texts reach out from the abstracted landscapes and topographies to tell of the extraordinary resistance of young women and girls leading the resistance in Iran. Similarly, long, lyrical swathes of black — another instance of Mehraban’s printmaking sensibility finding a home on the canvas — sweep through printed reproductions of social media missives speaking to the Women, Life, Freedom movement.

The carpets are there, too. Three Persian miniature rugs, framed but free of glass, rest in their half-arrested states, glue and gold leaf representing both bondage and prosperity.

South Africa, now 30 years into democracy, and only weeks away from its general elections, is still struggling under devastating economic and infrastructural hardship. In Iran, the government continues to target protestors, activists, journalists and others. Both countries promised a better quality of life for the majority in the years following their respective transformations but, as Mehraban points out, these promises seldom hold.

Sepideh Mehraban, ‘Beloved city’, 2021, Mixed Media on Canvas. Part of the artist’s ‘This is not Propaganda’ exhibition at SMAC Gallery. (Photo: Supplied)

Even more urgent is Iran’s recent retaliation against Israel, which has brought a great deal of speculation about war between the two countries. “For the last 45 years of the Islamic Republic, Iranians have had constant bad news,” Mehraban says via email. “It’s been either the possibility of war, sanctions, social-political pressure of incompetent governance of a theocracy rule, or dire economics. I do despise the government, but the last thing that I want is war.”

While the Iranian government is not representative of its people, she explains, citizens ultimately inherit the conflict, corruption, and inequality of their governing powers. Still, she remains resolute in her belief in a better world.

In this way, Mehraban’s carpets might be seen as speculative scenes: complex landscapes embedded with a rich cultural history that, despite being obscured and suppressed, are never without the possibility of a newly gilded future. DM

![]()

1 week ago

88

1 week ago

88