It is a hot Friday in the arid Northern Cape town of Churchill, and Richard Itumeleng and Lorato Daphney are drinking a quart of Black Label with a friend outside the RDP house they share.

It is only noon, but there is precious little else to do in Churchill on days like this.

“The only work here is EPWP,” says Itumeleng, referring to the government’s Expanded Public Works Programme.

Now in its 20th year, the programme offers short-term job placements in infrastructure and maintenance programmes. Across vast swathes of South Africa’s rural hinterland, these are simply the only jobs available and are rotated among members of a particular community.

In towns like Churchill, it is no exaggeration to say that the only two measures keeping most residents from starvation are the EPWP and social grants.

This year, however, there is one further opportunity available: to be a temporary staffer for the Electoral Commission of South Africa (IEC) for the upcoming elections. Daphney got lucky and secured one of these coveted gigs, though neither she nor Itumeleng is sure if they will actually vote.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Elections 2024 – All your questions answered

Daphney reels off the problems they face: “There’s no roads. We only got water last year. There’s only Apollo lights [highmast floodlights]”.

Lerato Daphney (left) and Richard Itumeleng (right) outside their home in Churchill in the Northern Cape. 12 April 2024. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

Just down the road, in a building festooned with campaign posters, local ANC organisers are strategising. All women, several wear T-shirts emblazoned with the face of deceased former Cabinet Minister Tina Joemat-Pettersson.

Outside the Northern Cape, Joemat-Pettersson is remembered primarily for her role in orchestrating the aborted nuclear deal with Russia that almost locked South Africa into decades of financial serfdom. But in this province, to the ANC faithful, Joemat-Pettersson remains a political icon practically canonised in death.

ANC member Onalenna Matsioloko at the local ANC office in the rural settlement of Churchill, in the Northern Cape. She believes the ANC will win an outright majority in the 2024 provincial and national elections. 12 April 2024. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

Onalenna Matsioloko confirms the area’s challenges: “There are no roads; people are not working. The children finish Grade 12 and there’s no job, no nothing. The government tries, with learnerships and EPWP.”

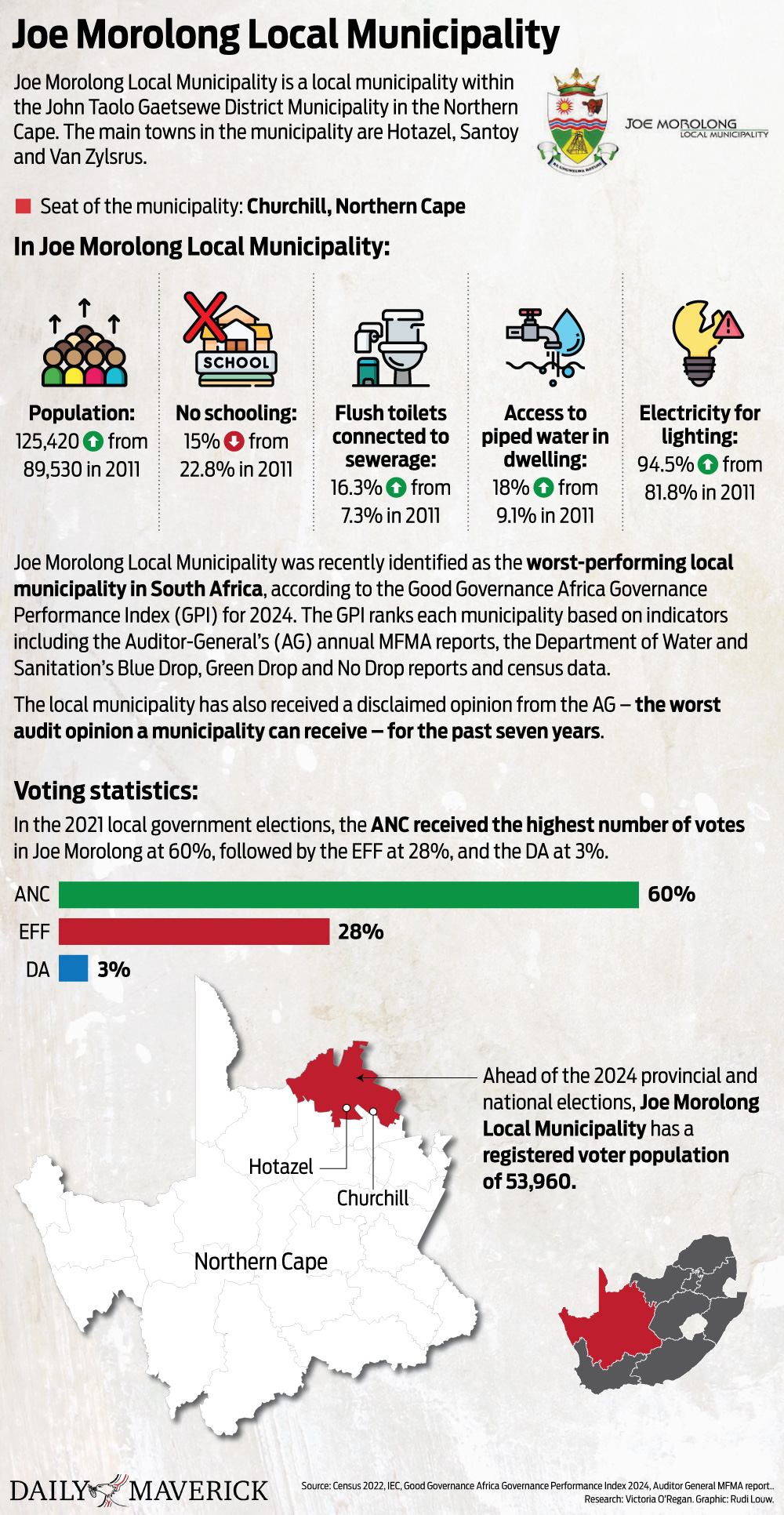

To campaign for the ruling party under these circumstances must be difficult, we suggest. This is a municipality in which support for the ANC dropped precipitously between the 2016 and 2021 local government elections: from 70.7% to 60.2%. EFF and DA votes have been growing steadily.

But Matsioloko pushes back on the suggestion that the ANC might be in trouble.

“People are angry, but not that much,” she says, while her four colleagues murmur assent.

“These are personal issues, not ANC. The elders want the T-shirts of the ANC. They wear the T-shirts.”

On the litter-strewn road into Churchill, a lone poster for Jacob Zuma’s MK party fluttered on a lamp post.

***

Joe Morolong Local Municipality, of which Churchill is the seat, is a national disgrace. In the Good Governance Africa’s Governance Performance Index 2024, it was ranked stone last for municipal performance in the category of “mostly rural local municipalities” across the country.

It received a disclaimed opinion — the worst audit opinion a municipality can receive — from the Auditor-General (AG) in her 2021/22 consolidated general report on the local government audit outcomes. Joe Morolong has received a disclaimed audit opinion for seven consecutive years.

The AG report in question singled out Joe Morolong for, among other things, squandering money on consultants: “Joe Morolong Local Municipality spent R14.64-million on financial reporting consultants that focused on areas where there were limitations in the previous year, but this did not have a positive impact because the municipality again failed to implement proper record-keeping controls in 2021-22”.

An MK party poster (far right) hangs on a telephone pole outside Churchill in the Northern Cape. ANC officials in the village say they are unconcerned about the presence of MK which will contest the 2024 elections, in the province. 12 April 2024. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

The report also found that it was a municipality which has “made little to no progress on infrastructure projects due to cashflow difficulties and poor project management”, and has also failed to secure what little infrastructure does exist, resulting in vandalism and theft.

Read more in Daily Maverick: Auditor-General slams Northern Cape municipalities’ ‘inability to manage their resources’

Most roads in Churchill, in Joe Morolong Local Municipality, are gravel and residents say the town lacks basic services such as water and electricity. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

But while Joe Morolong is a watchword for municipal neglect, incompetence and corruption, it simultaneously claims an unlikely title on the other end of the scale.

As BusinessTech pointed out in 2023, tax data suggests that the municipality boasts the highest median income in the entire country, at R34,599.

By contrast, the same data set puts the City of Johannesburg’s median income at R11,761 and the City of Cape Town’s at R8,290.

Joe Morolong, in other words, is both one of the richest and poorest places in South Africa.

***

A street in Hotazel, in the Northern Cape. According to local residents, there are 950 houses in Hotazel, of which only three are private properties – the rest are maintained by the Australian mining company South32. 12 April 2024. (Photo: Victoria O’Reg)

The town of Hotazel is only around 70km down the R31 from Churchill, but in experiential terms, it may as well be on another planet. Green and orderly, it has an air of peaceful prosperity. Driving around its quiet streets, one quickly realises how this place appears to thrive from within its ailing municipality.

“The whole town is owned by the mine,” Ruan Langeveld told us.

Langeveld, 28, was braaiing skilpaadjies — a Northern Cape speciality, consisting of liver encased in fat, and much more delicious than they sound — for sale on the road outside a guesthouse.

Throughout Hotazel, signs bear the imprimatur of the town’s real controllers: South32, an Australian mining giant with operations on three continents. In Hotazel, it mines manganese.

“If the lightbulb in your house goes out, you call the mine,” said Langeveld, who was only slightly exaggerating: of some 950 homes in Hotazel, you can count the number of privately owned properties on one hand.

Local businessman Ruan Langeveld (28) braais skilpadjies — lamb’s liver wrapped in ‘netvet’, which is the fatty membrane that surrounds the kidneys — in Hotazel, in the Northern Cape. 12 April 2024. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

“The mine maintains everything; all basic services,” Langeveld told us. He pointed up the road, to a tiny hokkie — not even a proper building — with a queue of people snaking around it.

“That’s the municipal office. The only thing they do there is write up proof of addresses for people.”

In the Kalahari mining basin of the Northern Cape, we heard the same thing repeatedly. If you want something done, infrastructure fixed, or a basic service supplied, forget about talking to the municipality. You call the mines.

The town of Hotazel in Joe Morolong Local Municipality, in the Northern Cape, is quiet and pristine on the morning of 12 April 2024. Joe Morolong Local Municipality is regarded as the worst municipality in the country, and has received disclaimed audit opinions from South Africa’s Auditor-General for several years in a row. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

“There’s a lot of money here. But if the mine isn’t here, there’s nothing else for the rest of the community,” Langeveld said. He was building a kind of business empire locally; his latest project was to develop a shopping centre locally.

On a parallel road to Langeveld’s skilpaadjie stand, 33-year-old Patrick Koboekae sat behind the reception of the town library. It was small but neat and well-resourced.

“The mine,” Koboekae confirmed, adding that the library fell under the management of the mine’s rec club.

Patrick Koboekae (33), a librarian at the local library in Hotazel, Northern Cape. The Hotazel library is subsidised by the Australian mining company South32. 12 April 2024. (Photo: Victoria O’Regan)

“Mostly people come in for copies and emails. And kids come and do their homework here.”

Koboekae said that he had been living in Hotazel for two years, and had no intention to leave. In the benighted wider landscape of the Joe Morolong municipality, he was well aware just how much of an oasis Hotazel seemed.

“It’s a quiet place. It’s a good place.” DM

Daily Maverick’s Election 2024 coverage is supported, in part, with funding from the Friedrich Naumann Foundation and vehicles supplied by Ford.

![]()

1 week ago

95

1 week ago

95