This report is based on a cache of leaked documents from the Eswatini Financial Intelligence Unit.

- More than R2-million of ANC-linked money may have flowed to Eswatini’s deputy prime minister, #SwaziSecrets leaks suggest.

- Controversial Archbishop Bheki Lukhele seemingly acted as “God’s launderer”.

- The leak shows that banks and the Eswatini Financial Intelligence Unit did their job, but law enforcement was nowhere to be seen.

In 2018, self-proclaimed Archbishop Bheki Lukhele officially opened the headquarters of his All Nations Christian Church in Zion in Ezulwini, a town near Mbabane, the capital city of Eswatini.

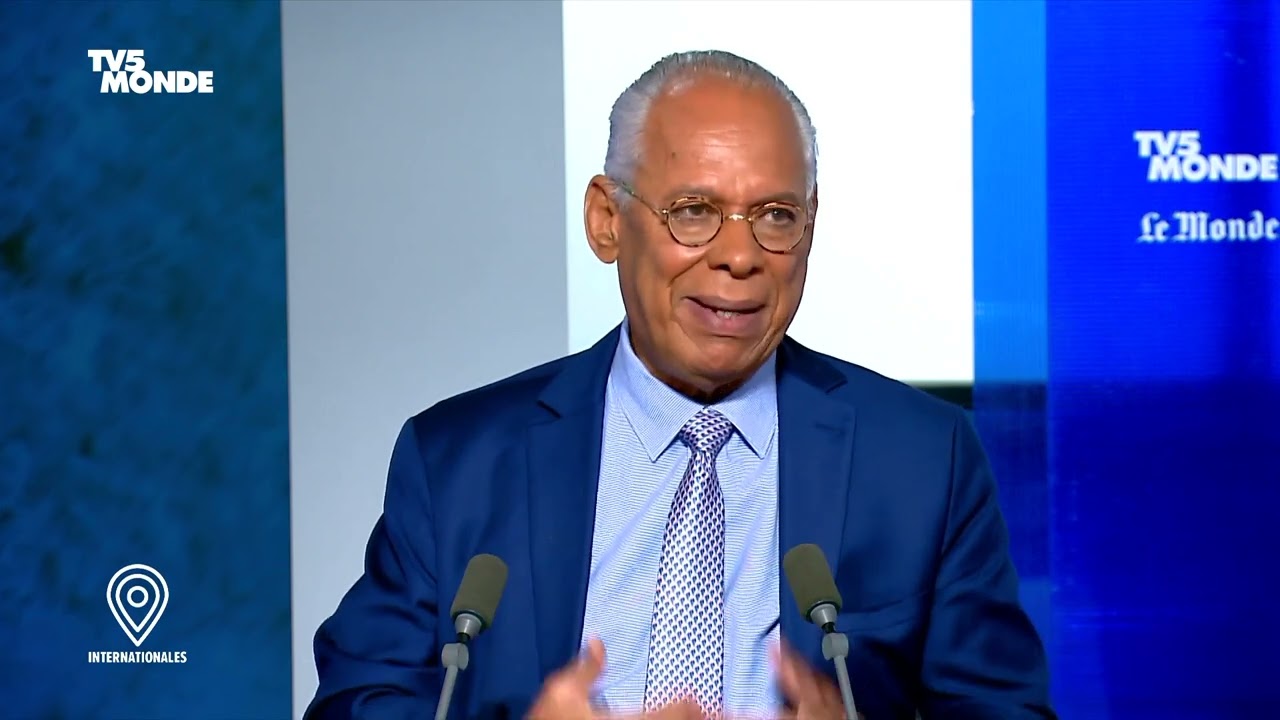

Controversial Archbishop Bheki Lukhele. (Photo: All Nations Christian Church / Facebook)

Reports indicate that All Nations erected at least two church structures that year, the second in South Africa’s KwaZulu-Natal province.

A year later, the headline of an article covering the opening of another new building in an area of Eswatini called KaShoba declared: “No Evil Money With Bishop Lukhele – Chief.”

According to the article, “rumours” had been circulating that Archbishop Lukhele held “evil money,” and the chief of KaShoba wanted to set the record straight.

All Nations Christian Church. (Photo: Yeshiel Panchia / ICIJ)

Now, a leaked cache of financial intelligence documents seen by amaBhungane suggests the rumours were not so far off the mark.

Not only was the source of Lukhele’s money suspect, but so were some of the beneficiaries.

Lukhele’s bank statements show that he regularly doled out cash to “prominent” politically exposed persons in the kingdom, including members of Eswatini’s parliament, the then mayor of Mbabane, and, most significantly, former Deputy Prime Minister Themba Masuku.

It appears that Masuku received over R2-million from Lukhele between 2018 and 2020.

The money flows started while he was still the administrator of one of Eswatini’s four regions, Shiselweni. The role of regional administrator in Eswatini is similar to that of a South African provincial premier.

AmaBhungane’s investigation shows that the first payments happened about five months before Masuku was appointed deputy prime minister and continued throughout his term of office.

More Swazi Secrets

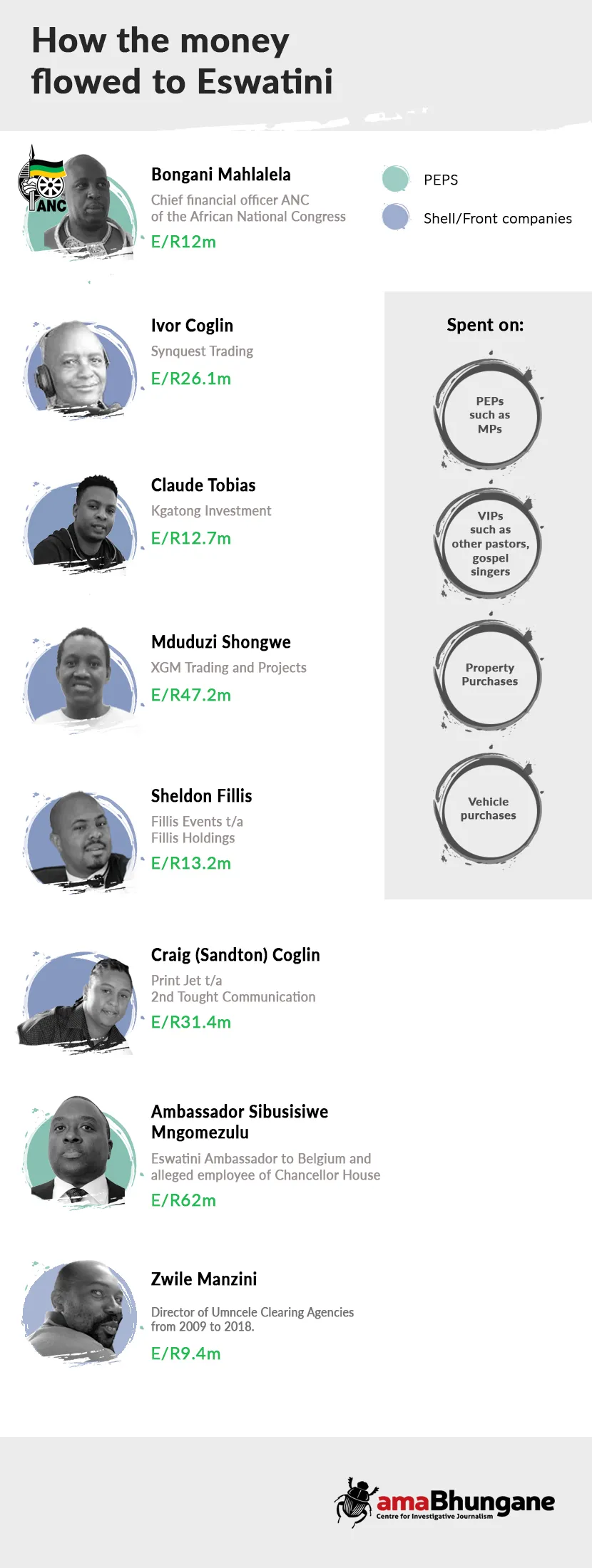

In Part One of our investigation, we chronicled how Lukhele received over R200-million between 2015 and 2021 from a cluster of suspected front companies ostensibly controlled by individuals who had access to the coffers of South Africa’s ruling African National Congress (ANC).

Swazi Secrets is an investigative project coordinated by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The project is based on 890,000 leaked documents from Eswatini’s Financial Intelligence Unit (EFIU), which ICIJ shared with a team of 38 journalists across 11 countries.

The EFIU is a statutory agency responsible for gathering, analysing and distributing intelligence about suspicious transactions to the relevant authorities in an effort to combat money laundering and terrorism financing through the kingdom’s financial system.

Bank statements from the leaks reveal how a stream of deposits to Lukhele’s personal and church accounts caught the attention of Eswatini’s financial regulators, whose subsequent probing uncovered a suspected money laundering scheme implicating the ANC’s head of finance, Bongani “Bongo” Mahlalela, as well as his good friend Sibusisiwe Mngomezulu.

Mngomezulu is the brother of one of King Mswati’s wives, Sibonelo, known as Inkhosikati LaMbikiza. He is currently Eswatini’s ambassador to Belgium and previously worked as an executive in the ANC’s investment arm, Chancellor House Holdings.

Leaked documents from EFIU reveal how traces of Lukhele’s riches lead back to the ANC’s Election Fund account, aided by the ambassador and the ANC money man.

Now, in Part Two, we go to Eswatini and try to trace where some of the money went, while uncovering the techniques Lukhele appears to have used to conceal what he was doing.

In addition to politicians, Lukhele appears to have made payments to several police stations, popular gospel singers and pastors.

A transaction analysis of Archbishop Lukhele’s bank statements shows that once the money was in the man of God’s accounts, he engaged in what appears to be further laundering through unusual, complicated transfers and purchases.

It is difficult to pinpoint where most of the money ultimately ended up, due to the complex transfers Lukhele made to himself and various beneficiaries.

Who is Archbishop Rebios Sigaca Lukhele?

Archbishop Lukhele is something of an enigma. You will struggle to find any online reports about the man or his church from before 2017, not even from people who belong to the church.

The earliest signs of Lukhele’s existence as a church leader come from two dormant church accounts on Twitter and Facebook that were created in 2017.

In August 2017, the church invited the Swazi public to an official ceremony where they opened what appears to be the church’s first substantial structure in the town of Bethany.

This was also around the time that Lukhele began to attract a lot of public attention.

From 2018 onwards, the publicity around Lukhele established him as a polarising celebrity church leader in Eswatini.

Local media headlines ranged from expressing awe about his generous donations and offers to charities and fellow pastors in Eswatini to allegations that he was on a mission to buy churches in the country and merge them with his own.

The criticism also extended to his personal life and practice of polygamy after he married the late award-winning gospel singer Mayibongwe Mthimkhulu, his fourth wife, in 2019.

“The man is alleged to be buying buses cash by simply swiping his personal ATM card at the garages in South Africa and the [Swaziland Revenue Authority] is aware of this. How can the SRA allow a Swazi to have millions with no verified source in a simple personal account?

“Is the man controlling money for himself or someone powerful in Swaziland?” asked one senior pastor in a news report where Lukhele claimed his money was “clean”.

Information about how big the All Nations Church is, both within and outside of Eswatini, is inconsistent. The numbers range from between 30 to 60 branches and there is no information clearly defining the church’s footprint on its official social media pages.

In December last year, amaBhungane visited the All Nations headquarters in Ezulwini on a sizeable piece of land close to the main road.

The entrance to the All Nations Christian Church in Zion. (Photo: Yeshiel Panchia / ICIJ)

All Nations Christian Church in Zion. (Photo: Yeshiel Panchia / ICIJ)

The church’s main structure is a large, rudimentary hall set on top of a hill, while another smaller building can be found at the bottom. Most of the land is open or used as parking, with a few branded buses visible in the yard.

The main church looks like the hall in Bethany that was unveiled in 2017, and also like the South African branch in KwaZulu-Natal seen on the church’s Facebook pages.

‘Extremely alarming’ money flows

Defending the legitimacy of his money, Lukhele told Swaziland News in 2019 that he was open to an investigation into his financial affairs, adding that he had already been approached by the Royal Eswatini Police Service, who were “satisfied with how he earns a living”.

“I can confidently confirm that my money is clean because it is received through the banks… it is traceable with all the proof. I don’t deposit money to the bank in cash except for the church offerings,” said Lukhele.

Lukhele, who was also the owner of one of Eswatini’s biggest soccer teams, Mbabane Swallows, from 2019 until recently stepping down, said that “offerings in the Zion church” were not much.

He claims his true source of income came from the shares he held in companies and the rent he received from his properties in South Africa and Eswatini.

But, as we laid out in Part One, leaked documents show that banks had been flagging the large volume of deposits in Lukhele’s accounts since at least 2017.

One report submitted to the EFIU by First National Bank (FNB), flagging the suspicious transactions, described the deposits in Lukhele’s account as “extremely alarming”.

In fact, the over R200-million in unexplained money flows from South Africa that ended up in Lukhele’s various FNB and Nedbank accounts were so concerning that, at different points, the two banks terminated their relationships with him.

Chief among the banks’ concerns was the discrepancy between the source of income Lukhele had declared and what he was receiving. The way he spent and transferred the money between the accounts he controlled was even more startling.

Manna from heaven

After FNB traced the origins of some of Lukhele’s cash infusion to the ANC’s election fund account, the EFIU not only reported these findings to South Africa’s Financial Intelligence Centre (FIC) for further investigations but also submitted reports to Eswatini’s law enforcement authorities and tax agency.

The reports laid out several theories or suspicions about these deposits.

The EFIU said Lukhele was possibly working with the ANC’s CFO Mahlalela and King Mswati’s brother-in-law Mngomezulu to “siphon” money out of an elections account belonging to South Africa’s governing party and then hiding that money in property purchases in Eswatini.

Alternatively, regulators suspected that if Mahlalela was working on behalf of the party, it meant “the ANC is involved in concealing or hiding the funds in Eswatini using Mr Lukhele”.

However, almost religiously, after receiving a payment Lukhele would break it up into smaller, mobile money and electronic transfers, many of which looked like salary payments for church members.

Larger chunks of money were spent on acquiring property and luxury vehicles in South Africa and Eswatini.

Lukhele, through various accounts controlled by him, also made substantial cash withdrawals between 2015 and 2022.

Inflated property

One technique that Lukhele seemingly used to obscure the ultimate beneficiary of the money moving out of his accounts was through property purchases where, on occasion, he transferred two or three times more money than the stated purchase price.

Records obtained by amaBhungane suggest that Lukhele paid R55.4-million for properties worth only R28-million. Channelling money through exorbitant real estate transactions is a classic red flag for money laundering.

This R55.4-million is reflected in various transfers made to his attorney, Andreas Mfaniseni Lukhele, that were explicitly labelled as property payments, while R28-million is the total value of properties we could find bought by him or his corporate vehicles in official deeds office documents.

Twelve of these properties were bought in Eswatini and one in South Africa. All were bought after 2017 when the suspicious money flows we documented in Part One started reaching high volumes.

The properties bought between 2018 and 2019 made up the bulk of the purchases, totalling R24.4-million, according to deeds documents.

References in statements make it unlikely that there are other properties comprising the difference.

Moreover, the commercial buildings we found were mostly occupied by Lukhele’s own companies, undermining his claims of massive rental income.

The deed transfer documents that we obtained show that the Archbishop’s lawyer, Andreas Mfaniseni Lukhele of Dunseith Attorneys, was the transferring attorney responsible for the sale of all but one of Lukhele’s properties in Eswatini.

The Deputy Prime Minister

Andreas was also the transferring attorney in a June 2020 property sale where Lukhele bought a farm from former Deputy Prime Minister (DPM) Themba Masuku.

The farm was bought at a seemingly grossly inflated price, possibly to partially disguise payments transferred to Masuku two years earlier.

It worked like this:

- Deeds documents show that Lukhele’s company was the buyer of a farm in the Shiselweni region, where the DPM used to be an administrator.

- The company paid R1.35-million for the property, which was owned by Masuku’s Lawuba Investments (proprietary) Limited.

- No money left Lukhele’s account in June 2020 or around that period to pay for this transaction.

- Instead, in June 2018, Lukhele, through two payments in that month, transferred R2.7-million to Howe Masuku Nsibande Attorneys, where the DPM’s son was a partner. These deposits were labelled “Ra Masuku”, short for Regional Administrator Masuku.

- Shortly after those payments were made, Masuku’s bank statements show that he received payments of R1.31-million and R1.44-million from his son’s law firm.

- In addition, Masuku’s statements reveal that he received R55,000 directly from Lukhele in July, August and November 2018.

- Masuku received another R30,000 in June 2020 and R15,000 in December. These payments were referenced “Dpm”, short for deputy prime minister.

- Deeds records show that Masuku’s company bought the farm in June 2019 for just under R100,000. A year later, he sold it to Lukhele’s Mbhiji Investments for the aforementioned R1.35-million.

Ex-Deputy Prime Minister Masuku received amaBhungane’s questions but did not acknowledge receipt or respond. Similarly, questions sent to Howe Masuku Nsibande Attorneys, and now Judge Sabelo Masuku, weren’t answered.

Dunseith Attorneys and the other properties

As mentioned earlier, the rest of the property transactions seen in Lukhele’s personal All Nations and Sigaca Trust accounts reveal that he paid an estimated R55.4-million to Dunseith Attorneys between 2018 and 2019 for properties apparently costing only R28-million.

An additional R12.5-million that was paid to Dunseith is excluded from these figures because the references on those payments were not clearly for property purchases.

The figures also exclude payment made toward Lukhele’s property in Pietermaritzburg.

To illustrate, in July 2019, according to property records, Lukhele bought a R9.4-million property through his investment company from an agency called Leittes Properties. However, Lukhele’s bank records show that he transferred just under R24-million to Dunseith, referencing “Leittes Properties”.

Another example where there appears to be a discrepancy in the listed price and what Lukhele ultimately paid is his Dalriach property, where he appears to have bought different sections in three transactions between 2018 and March 2019.

The property’s purchase price is listed as R6.4-million at the deeds office. However, transactions in Lukhele’s account reveal that he paid Dunseith a total of R22.3-million, using the reference “Dalriach”.

In other words, Lukhele appears to have made transfers to his attorney, Andreas Lukhele, that were R14.6-million more than he needed to pay the seller for the Leittes property transaction and R15.9-million more for the Dalriach property.

It gets messier when considering that both the Archbishop and Andreas Lukhele, who is now a judge of Eswatini’s Industrial Court of Appeal, are also listed as co-directors in three companies, including the football club Mbabane Swallows.

Andreas was also a signatory of the All Nations Church bank account.

The nature of the Archbishop’s property transactions likely substantiates the concerns flagged by Nedbank in a suspicious transaction report in 2021.

Nedbank flagged an issue with the overlapping relationship between Lukhele and his attorney and further noted that Andreas Lukhele had “certified most of Lukhele’s documentation” that he had submitted to the bank’s compliance department.

Moreover, the Nedbank report explained that they had also reported the lawyer for an unrelated and relatively trivial matter. In their report, they noted, in reference to Lukhele, “we suspect that he is also assisting our client to launder his funds”.

Andreas told amaBhungane that he would not be answering questions about work he did as an attorney, despite being the founder and owner of Dunseith.

Buying cover for an unknown agenda?

There were also other smaller transactions traced to prominent individuals and institutions in Eswatini society that were noticed by regulators.

Among Lukhele’s litany of recipients was the mayor of Eswatini’s capital, Mbabane, who occupied that position for multiple terms between 2009 and 2023. Mayor Zephaniah Nkambule received in excess of R400,000 from Lukhele between 2017 and 2019, according to bank statements.

Another beneficiary of Lukhele’s generosity was Strydom Mpanza, yet another member of parliament, who received R370,000 between 2018 and 2019.

Businessman Robert Magongo, who received deposits totalling R116,500 between 2017 and 2022, was a parliamentarian when he received all these payments apart from one.

Former mayor Nkambule and Mpanza did not respond to questions. Magongo told amaBhungane that he had never received money from Lukhele and he didn’t know the man.

Lukhele’s bank records also show that between 2017 and 2019 he made payments of over R410,000 to several police stations in areas such as Siteki, Gama, Ngwenya and Malkens, as well as Nhlangano Royal Police Station.

Sometimes these transactions were referenced as “police gospel” or “police band”.

The EFIU concluded that “Lukhele might be inducing the political exposed persons, pastors, gospel artists and general public who are beneficiaries of the funds to gain support, power and influence in whatever agenda he is pursuing with his accomplices.”

Together in the crooked place

Lukhele didn’t only engage in suspicious transactional behaviour through his own accounts. Instead, leaked EFIU reports and documents reveal that he roped in his family members and associates, too.

This included his wives, Gugu Ndzabandzaba and Mayibongwe Mthimkulu, his brother Thulani “Kabasa” Lukhele and his son Ncamiso Lukhele, who was also a co-director of the church.

Both Lukhele’s brother and Mthimkulu are dead. Questions to Ndzabandzaba and Ncamiso were sent via Lukhele, who did not respond on their behalf or for his part.

The activity in the accounts belonging to Lukhele’s associates shows that they sometimes received funds from the same front companies reported in Part One. These companies, directly and indirectly, sent money to Lukhele and distributed this money through the same pattern of cash withdrawals and transfers seen in the Archbishop’s accounts.

A report looking at Ndzabandzaba’s account activity in April 2020 noted that whereas she normally received R8,000 in her account for “maintenance”, she had started to receive “numerous deposits from various accounts all connected to one Mr Bheki Lukhele,” who had previously been flagged for suspicious transactions.

“These funds as received by Ms Ndzabandzaba were then withdrawn in full almost immediately, at one point E1,000,000.00 was withdrawn via teller. The suspicion surrounds the true source of funds as well as the flow through of funds seen,” reads the report.

Between April and May 2020, the activity in Lukhele’s son’s account was also flagged. For instance, FNB pointed out that Ncamiso’s turnover in April rose to over R1.5-million, “which is substantially higher than previous months”.

“These funds then withdrawn via bank teller immediately and in full, which is suspicious as it would be simpler and safer to use digital platforms to transfer funds. These funds bear a name suggesting that the funds come from his father, or an account where his father is a signatory.”

Calculations looking only at cash withdrawals from Lukhele and his family members’ accounts show that between 2015 and 2021 they withdrew close to R20-million in cash, in some instances making explicit requests for rand-denominated notes.

One example of this was detailed in an FNB report focusing on Lukhele’s late brother, Thulani.

On 5 August 2020, Thulani received a R1-million deposit from a suspected front, XGM Projects. We reported on how this company had sent millions to Lukhele since 2015.

The FNB report stated that Thulani withdrew the money from XGM at a bank teller on the same day it was deposited.

“The client was adamant that he withdraws the funds in cash requesting South African currency and ruled out the option of doing a bank transfer in favour of another account instead of handling so much cash,” FNB noted.

The bank report added that the transaction was suspicious in part because of its size, but also because “the source of funds to start with as it is not clear and is suspected to be linked to fraud or other… unethical behaviour”.

Accounts

The Swazi Secrets documents show that Lukhele began with three personal bank accounts held with Eswatini’s FNB.

In 2018 he opened an account for All Nations, as well as a family trust account.

One possible reason why the banks were not entirely able to identify the legitimacy of the money flows to Lukhele is that the Archbishop repeatedly misled these banks about his source of income and how much he would be receiving through his accounts.

In February 2017, Lukhele signed an FNB declaration form stating that his source of income was limited to R500 which he expected to receive as “proceeds from his own business”.

In the same month, he also submitted a letter confirming that he was a director and employee of Synquest Trading, where he said he earned R35,000 a month. Synquest is one of the suspected front companies that sent millions to Lukhele between 2015 and 2021.

When Lukhele opened personal and business accounts at Nedbank between 2019 and 2021, he was, again, also less than honest.

Across the signed compliance documents Lukhele submitted to Nedbank, he claimed to only be expecting income from a mix of the following sources:

- A monthly salary of R50,000 from his investment company, Mbhiji, including a R500,000 monthly turnover from “personal investments to start-up businesses and investments made in various sister companies”.

- Proceeds from a burial insurance company registered in South Africa, I Care Funeral Policy, of R200,000 a month.

- Rental income amounting to a total of R450,000. This was split between R250,000 in rental income from South Africa and another R200,000 from Eswatini.

- R100,000 a month from church donations.

- A mere R10,000 from “gate takings” at the matches of Mbabane Swallows football team.

I Care Cash Funeral Policy’s sole director is Nomlindelo Msomi, popularly known as “Rev Dr Lee M KaGcugcwa”.

Msomi is the leader of the most visible All Nations branch in South Africa based in Thornville, Pietermaritzburg. She is also a co-director of the church’s registered company in South Africa.

Lukhele’s bank records show that between 2019 and February 2022, Msomi transferred R6.2-million to Lukhele under the reference “Dr Lee”.

These money flows, largely beginning in late 2021, were flagged as suspicious by Nedbank, which said in a money laundering report that “there is no justifiable reason” for the transactions.

Msomi has in turn received R4.8-million from accounts controlled by Lukhele between 2018 and 2022, which, she told amaBhungane, was for building the Thornville church and funding supporting activities such as rental buses for events like Easter services.

On the money to Lukhele, Msomi said I Care was her company and quite profitable.

Accountability?

There are signs in the leaks that efforts were made to determine whether Lukhele’s income was legitimate and to pause any further laundering that he could be carrying out, but once the information reached the relevant law enforcement agencies, it hit a dead end.

Despite being aware of Lukhele’s “infracted accounts” since 2018, Eswatini’s tax authority told the EFIU in 2021 that, while its investigation was concluded, it didn’t know how to bill Lukhele “as there is fear of double taxation”.

“Funds are received from SA and only spent in Eswatini. The biggest issue now is that, are they funds taxed from source (SA), SRA now needs assistance from the [South African Revenue Authority] to check if subject has been taxed in SA for the period of 01 July 2015 to 30 June 2020, for them to conclude the case.”

The leaked records suggest that police have provided no updates to the EFIU since 2019, when they admitted that, when interviewed, Lukhele had provided “conflicting” accounts of his source of income.

The leaks also show that the Eswatini Anti-Corruption Commission (ACC) asked for more information.

Strangely, after the EFIU received a comprehensive report from South Africa’s FIC implicating the suspected fronts and ambassador Mngomezulu in seemingly facilitating illegal transactions, the ACC said this was not enough.

In a 2022 progress report about cases reported to the ACC, the Commission concluded that engagements with the FIC “did not yield any positive results as it was reported that [the FIC] indicated that there were no suspicious transaction reports reported in its jurisdiction in respect of these funds, thus they could not help.”

It is not clear from the documents whether any action has been taken in South Africa.

The FIC’s stipulated “media engagement approach” on its website makes it clear that “confidentiality requirements” emanating from legislation prevent it from “disclosing or denying” information about investigations and reports on specific cases.

Internal communication from Swazi Secrets shows that in 2020, the FIC requested permission to share the findings of the investigation into these money flows with the tax authorities and other law enforcement bodies.

By May 2022, Nedbank had seen enough and directed a letter to the EFIU informing the agency that it was in the process of closing Lukhele’s accounts.

“The termination followed an assessment made on Mr Lukhele’s accounts, in particular, the transactional activity observed in the said accounts,” Nedbank informed the EFIU.

“The bank holds the view that, in view of the client’s transactional activity and the absence of sufficient reasons to justify the noted activity in the accounts, it cannot continue its relationship with the client. There’s suspicion that he might be involved in money laundering or/and any predicate offence thereof.”

Internal communication shows that FNB had also begun the process of terminating its relationship with the Archbishop.

The Swazi Secrets documents show the EFIU largely doing their job as watchdogs against abuse of the financial system. It is the Eswatini law enforcement authorities who have seemingly shown little interest in following up on the forests of red flags.

Now that a clearer picture has emerged of the origins of Lukhele’s largesse, it remains to be seen whether their South African counterparts can do better. DM

Editorial support:

Lionel Faull, editorial coach, amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism

Troye Lund, managing partner: editorial, IJ Hub

Data support:

Miguel Fiandor, Jelena Cosic, Karrie Kehoe, Denise Ajiri, and Delphine Reuter, data team, The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Adam Oxford, data journalist, trainer and strategy consultant, OpenUp data journalism programme supported by Africa Data Hub

Main illustration:

Sindiso Nyoni, The International Consortium of Investigative Journalists

Multimedia:

Aragorn Eloff, digital coordinator, amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism

Tsholanang Rapoo, digital officer, amaBhungane Centre for Investigative Journalism

![]()

1 week ago

77

1 week ago

77