When we moved to Cradock, our new accountant, Tertius van der Walt, gave us a brief overview of what underpinned the town’s economy. Topping his list were the local schools.

A town with effective schools is economically blessed.

Parents from farms or smaller neighbouring towns come in to drop their children and then go on to do their banking and shopping. School events like dances, plays, concerts, athletics meetings, tennis tournaments and rugby matches attract parents and friends who stay over in guesthouses. Butcheries, supermarkets and restaurants all benefit.

Teachers are, obviously, employed, but each school also creates a dozen or more non-teaching jobs, depending on the size.

Schools need transportation and buses, generating jobs for drivers and mechanics. Seamstresses make and repair uniforms. Tutors and coaches are needed to help with certain subjects. Children buy snacks from tuck shops and tea rooms. If there’s a rugby, hockey or squash team, a capable physiotherapist is also needed.

Good schools attract young families to towns, and this brings energy and investment.

Cradock High School plays a huge part in keeping this Eastern Cape town whole and healthy. Image: Chris Marais

Platteland pups

The first thing my partner Chris and I noticed about children in the platteland is how polite and kind they generally are. They come across as well adjusted, friendly and respectful, mostly able to hold up their end of a conversation with adults of any generation.

Dad and kids enjoying poultry antics in the fresh air of the Little Karoo. Image: Chris Marais

Jeremy and Sharon Witts-Hewinson, both teachers who left Cape Town and moved to Klaarstroom in the Western Cape to raise their daughter Edwina, ascribe the pleasant nature of rural children to a number of factors.

“It may be because there are fewer distractions from the complexities and materialism of city life. Perhaps it’s simply because parents are able to work from home and have more time for them,” says Jeremy.

“For example, we live 52km from where our daughter Edwina went to school and where Sharon teaches, but it only takes half an hour to get there. Also, the kind of person who ups sticks and moves out of the city is probably seeking more connection and quality family time anyway.

“The exposure to different generations might also play a role. Because there are simply fewer people around, the children relate to everyone, not just those in their immediate age range.

“They grow up in the fresh air, literally closer to Nature, running around outdoors. They are exposed to ‘danger’ in play as they climb high trees, swim in the river or encounter large farm animals. They are not hemmed in by palisades and city security concerns. This seems to make them more self-reliant and generally resilient.”

“The secret to happiness in a small town is to live with less and to value simplicity more,” says Jeremy Witts-Hewinson.

Innocence and freedom

When Dave Ker of Johannesburg and Lisa Antrobus of Cradock married, they chose to start a family in her hometown.

“Out here, children stay children for longer” says Lisa. “There’s no rush to grow up. There are plenty of other advantages too, like how close everything is. In less than 20 minutes we can be picnicking in a national park. There’s a lot of extracurricular stuff here that you probably wouldn’t easily find in cities, like horse riding and river paddling, and it costs way less.”

Bev Collett, who grew up on a farm outside Cradock, left to work and study in Durban and Port Elizabeth where she met her husband Andre Muller. She still misses aspects of city life, but says raising her two children on the family farm was the right choice for them.

“They’ve grown up innocent and free. Our kids are always outside, building forts or swimming or climbing trees. I don’t worry when they go for walks in the veld or ride their bikes on the farm roads.

“When city friends visit, I notice their children don’t know how to play outside. They have no clue how to entertain themselves without a smartphone, a tablet or a television screen.”

Bev adds that another advantage is that excellent remedial teaching is available in the country for a pittance compared with city rates.

Life in a small town offers a closer, easier connection to the outdoors and to other children. (Photo: Chris Marais)

“And because everyone knows everyone, teachers are generally more invested and treat the children as if they were their own.”

Tertius van der Walt’s wife, Annemie, adds:

“In the platteland, teachers and parents tend to know each other outside the school grounds. They meet in the shops or at social gatherings, where an informal chat about a child often sorts matters out matters easily.”

It takes a village

If you want to glimpse the best of family life in the platteland, you could parachute in on the weekly tennis gathering at Fish River Station, about 50km north of Cradock.

This is an old-fashioned farming community, the centre of which is the low-slung tennis club, wedged between the river and railway siding of that name. In many parts of South Africa, similar social clusters have disappeared or diminished. But here, things still happen as they have for generations. Irrigation from the river allows more intensive agriculture of pecan nuts, lucerne and sheep, so there are also plenty of young farming families in the district.

Generations of farmers have grown up here, with children bonding from toddlerhood onwards.

Around the all-weather courts (people are terribly serious about their tennis here), there is the ebb and flow of dummies, spoegdoekies, nappies, prams and, most importantly, advice and support. There are always outstretched arms for a crying child.

Saturday afternoons offer blessed relief for Fish River mothers. They can come together and casually take turns to watch each others’ children. Talk revolves around the latest rains, Caesarean scars, school news, the wool prices, and the perennial subject of whether amber or biltong is best for teething babies.

Meanwhile, kids of all ages run in a small swarm around the club, the hedges and tall trees, the stone Methodist church, then off to a nearby swimming pool. They launch kites on windy days, but they also make up wildly imaginative games with an endlessly evolving script.

You’ll seldom find a child absorbed in a smartphone – not because it’s forbidden, but because it’s so boring compared with real life.

An astonishingly high percentage of Fish River children have gone on to become head girls and head boys at some of South Africa’s top schools.

Individual attention at Orange Grove School outside Tarkastad. (Photo: Chris Marais)

Country-raised vs. city-raised

Sports coaches often remark that farm children in particular are stronger, better coordinated and more agile than their urban counterparts.

Small-town children also seem more socially adaptable, especially those who have gone to racially mixed schools. Jurie Taljaard, a parent of two who has taught in Cradock and Grahamstown, said he noticed that country-raised youngsters adjust surprisingly well to tertiary education in larger centres.

Jeremy and Sharon Witts-Hewinson have noticed the same thing.

“Because of social media and television, city life gets its fair share of exposure in the smaller areas. Our children suss out urban ways quite quickly.”

City kids not so much.

“Urban children aren’t afforded similar insights into reality beyond their suburbs. The older teens seem to think their rural counterparts are just not cool,” says Sharon.

This makes it more difficult for city teenagers to adapt to country living in the last few years of formal schooling.

Klaarstroom, Western Cape, where residents Jeremy and Sharon Wits-Hewinson say urban teens often struggle to adopt country ways. Image: Chris Marais

The choice of schools

There are four main education choices in the platteland: Government “Model C” schools, small private schools, boarding schools in larger towns (private or government) and homeschooling.

Before you settle on a town, do some serious research on what kind of education would best suit your young family.

It’s worth noting that some of the country’s best schools are in rural areas – towns like Nottingham Road, Bedford, Graaff-Reinet, Cradock, White River, Paarl, Greyton, Vaalwater, Prince Albert, Tarkastad and Grahamstown.

One of the first issues most parents face is home language for education. This and the prospect of placing small children in boarding schools often sway choices in favour of homeschooling.

It is a growing phenomenon in remote areas, with latest figures in South Africa estimated at between 50,000 and 100,000 homeschoolers. Parents can choose from a number of educational support systems. Children from grades 9 to 12 write their examinations at designated centres that are invigilated.

The results can be highly variable for children. Some end up with a skewed worldview and large gaps in their knowledge base. Others get a sterling education that can take them right up to Cambridge A and O levels.

What about interaction with other children? In some areas, there are homeschooling tutor centres and parents collaborate to bring kids together every week for sports.

“The best thing is that I get to spend a lot of time with my kids – and every moment is a learning opportunity,” said one of the homeschooling mothers of Cradock, Angela Collett. DM

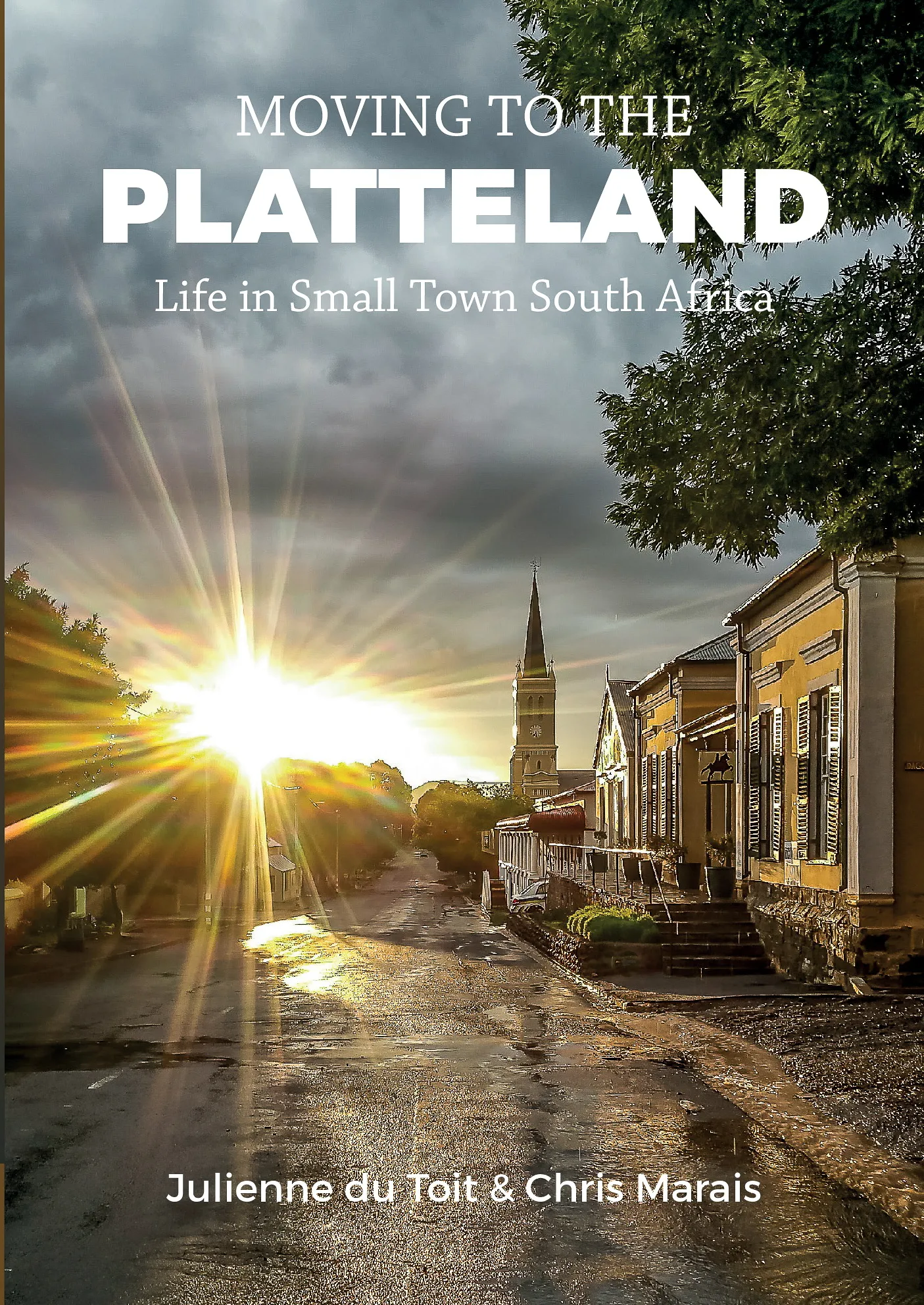

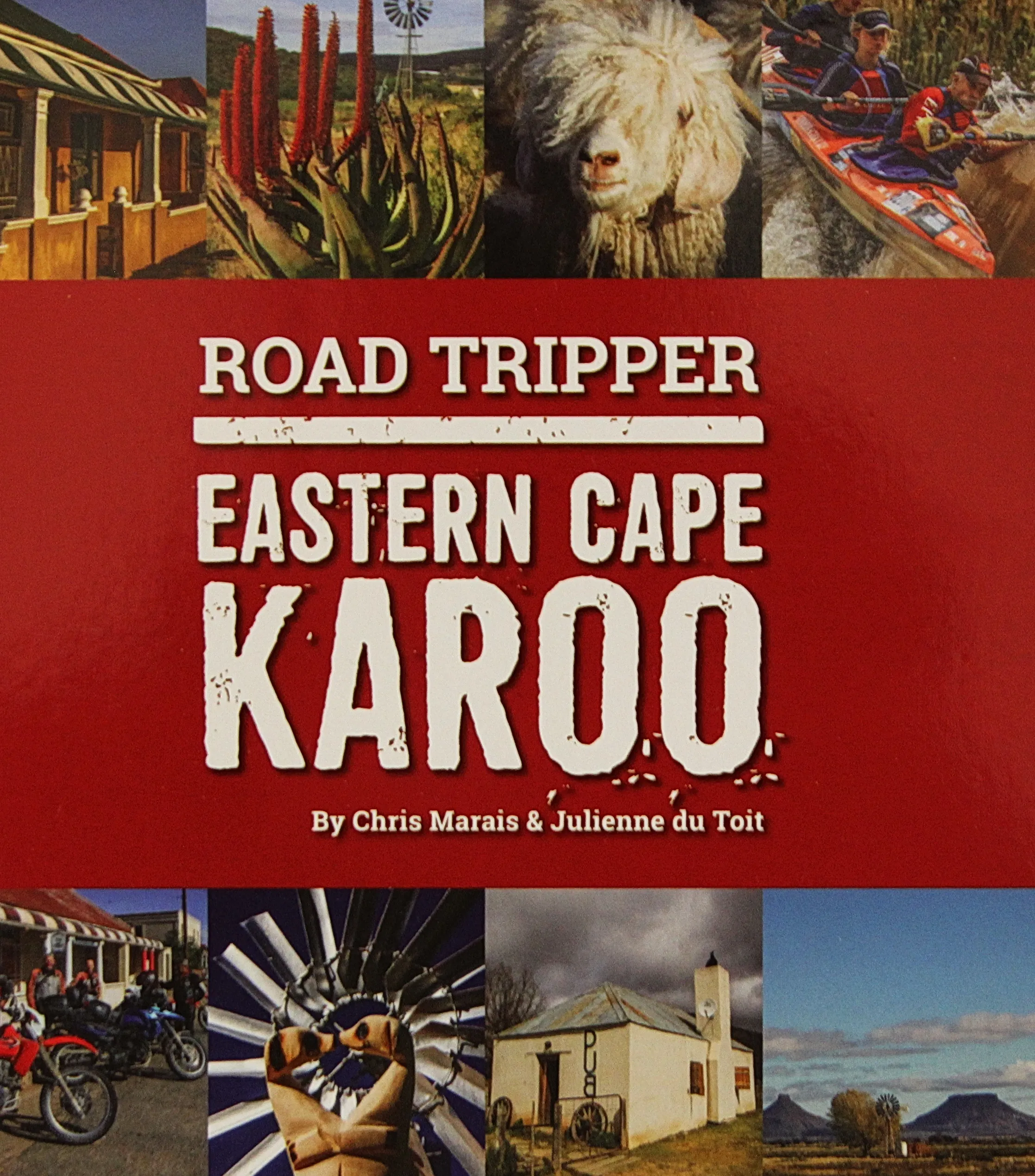

This is an extract from Moving to the Platteland – Life in Small Town South Africa by Julienne du Toit and Chris Marais. For an insider’s view on semigration and small town life in South Africa, get Moving to the Platteland and Road Tripper Eastern Cape Karoo (illustrated in black and white) by Julienne du Toit and Chris Marais for only R520, including courier costs in South Africa. For more details, contact Julie at [email protected]

![]()

1 week ago

67

1 week ago

67